This is part two of a set of posts breaking down some of the decisions I made when putting together the web server for townsourced. The first part is here.

Instead of a general overview, like part one, this post will focus specifically on User Authentication, i.e. how to handle passwords (if at all) and session management.

Password Management

The best, and most secure system for managing passwords in a web app is not to manage passwords at all. The most secure and bulletproof password system is still vulnerable to your user’s fallibility, and as you’ll see when we go over password management below, most of the work goes into trying to protect the users from themselves.

So, how do you get out of the password management business? You offload the work to trusted third parties. This usually means integrating OAUTH into your authentication code.

OAUTH

You’ll want to use popular third parties through which your users will probably already have accounts set up. My policy is

to give users as many options as possible so that the simplest option for them is to not create a password in my app.

This means adding OAUTH support for one or more of the Big Three.

- Facebook: Manually Build a Login Flow

- Google: Google Sign-In for server-side apps

- Twitter: Implementing Sign in with Twitter

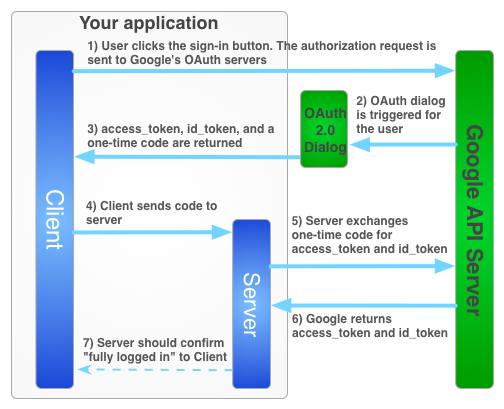

This will not be a detailed overview of implementing OAUTH, there are better articles out there for that. I will, however, step you through the pieces you need to have in place in order to get it working. A very high level overview of OAUTH looks like this (courtesy of Google):

Facebook and Google are very similar, and you should be able to get by with a standard OAUTH2 library (with a little bit of tweaking). Twitter, on the other hand, actually uses OAUTH1.0A, so you’ll need to make sure you use a library built for it like https://github.com/mrjones/oauth.

Each of the Big Three have a unique user identifier that you can store with your user record.

package app

...

type User struct {

Username data.Key

Email string

...

GoogleID string

FacebookID string

TwitterID string

...

}

And once that’s in place, you can do something like this:

package app

...

// FacebookUser gets a user (if possible) from the passed in facebook code

func FacebookUser(redirectURI, code string) (*User, error) {

fbSes, err := facebookGetSession(redirectURI, code)

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

//Lookup user in the database

usr, err := userGetFacebook(fbSes.userID)

if err == ErrUserNotFound {

data, err := fbSes.userData()

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

// Create new user from Facebook data

...

return newUser, ErrUserNotFound

}

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

// Return user and log them in

return usr, nil

}

Your Google and Twitter functions will look very similar. Check if a user already exists for the given third party credentials. If so, log them in, otherwise use the information shared (or accessible via some other API) to build a new user.

Passwords

If for some reason your user does not want to use a third party login, or you aren’t permitted to offer them in your app (for instance internal, non-internet facing apps), you’ll need to securely manage your users’ passwords.

Requirements

There is a lot of discussion, and argument over password best practices. I highly recommend doing your own research, to get a better understanding of the implications of some of these decisions before you start. Once again, the best option is to not to manage passwords at all. That being said, here is a short list of best practices I try to meet when setting my password requirements.

- Longer passwords are better than complex passwords

- Skip doing any complexity checks

- Don’t require a minimum level of entropy

- Don’t require at least one number or special symbols, etc

- Minimum password length should be 10, or even better 12 (as of 2015)

- No max length (more on handling that later)

- Skip doing any complexity checks

- Password should not be on the top 1,000 (or more) most common passwords list

Thats it.

Simple requirements are easier for your users to understand, easier for you to manage, and easier for you to rip out and rewrite when technology inevitably changes.

Recommended reading:

Implementation

Once again, there is a lot of discussion around whether you should hash your passwords using bcrypt or scrypt. If you are debating between these two, then you are off to a good start. Yahoo was apparently using MD5. Personally I went with bcrypt, but both scrypt and bcrypt give you good protections against modern attacks (with the ability to increase the work factor), while doing away with unneeded aspects of password management like salting.

However, there is one aspect of bcrypt and scrypt that you need to be careful of. By their very nature, these hashing algorithms take time and resources to process. They do this to make it hard to run large dictionary attacks. But this also leaves your web application vulnerable to a potential denial of service attack if a user submits a very large password. To protect against this, you could set a max possible length for user’s passwords, but that goes in the face of the rule above: Long passwords are better than complex passwords. Instead, we can pass the password through a sha512 sum, to guarantee that only 512 bits ever get passed through to bcrypt or scrypt.

Below is the implementation of this (with the optional third party authentication) in townsourced.

package app

...

/// UserLogin logs in a user via their password and either their username or email

func UserLogin(usernameOrEmail, password string) (*User, error) {

u := &User{}

if strings.Contains(usernameOrEmail, "@") {

//login with email

err := data.UserGetEmail(u, usernameOrEmail)

if err == data.ErrNotFound {

return nil, ErrUserEmailNotFound // can test for email, but not username

}

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

} else {

// login with username

err := data.UserGet(u, data.NewKey(usernameOrEmail))

if err == data.ErrNotFound {

// don't expose that user doesn't exist

// a bad password and an incorrect username should look the same

return nil, ErrUserLogonFailure

}

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

}

if u.HasPassword == false || len(u.Password) == 0 {

//User isn't a password based user, and can't login with a password

// they need to use facebook/google/twitter

return nil, ErrUserLogonFailure

}

err := u.login(password)

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

return u, nil

}

func (u *User) login(password string) error {

if !u.HasPassword || len(u.Password) == 0 {

if u.GoogleID == "" && u.FacebookID == "" && u.TwitterID == "" {

return ErrUserLogonFailure

}

// Can't auth password for non-password based users

return nil

}

// sha512 password and compare

shaPass := sha512.Sum512([]byte(password))

err := bcrypt.CompareHashAndPassword(u.Password, shaPass)

if err != nil {

if err == bcrypt.ErrMismatchedHashAndPassword {

return ErrUserLogonFailure

}

return err

}

return nil

}

Dropbox does something similar with their passwords, and they have a good writeup of their implementation here: https://blogs.dropbox.com/tech/2016/09/how-dropbox-securely-stores-your-passwords/.

Password Resets / Forgotten Passwords

Notice above, how there is no mention of security questions, or password hints. This is on purpose. Some of the biggest, most public “hacks” that you’ll read about online are almost always due to taking over accounts by looking up or guessing answers to security questions. The much safer, and simpler way for users to recover passwords is to use a recovery email request.

Generate a unique random token (make sure to use crypto/rand not math/rand) and email it to the previously verified email address of your user. In the email have the unique token passed through a URL that triggers a password reset if the token is valid. Tokens should be usable once only, and should eventually expire if not used.

//Random returns a random, url safe value of the bit length passed in

func Random(bits int) string {

result := make([]byte, bits/8)

_, err := io.ReadFull(rand.Reader, result)

if err != nil {

panic(fmt.Sprintf("Error generating random values: %v", err))

}

return base64.RawURLEncoding.EncodeToString(result)

}

Session Management

Now that you’ve authenticated your user, you’ll want to create a session so that they don’t need to re-login on every request. Just like with forgotten passwords and OAUTH, you’ll be creating a unique, cryptographically random, and expire- able token to identify a session. You’ll store that token in a cookie in the browser, and force an early expiration when the user logs out.

Here’s what the complete Session type looks like in townsourced. You’ll notice there is a bit more in there besides just the token (SessionID) and expiration.

package app

...

// Session is an authenticated session into townsourced

type Session struct {

Key string //userkey+sessionID

UserKey data.Key

SessionID string

CSRFToken string

Valid bool

Expires time.Time

When time.Time

IPAddress string

UserAgent string

user *User // cached user struct, to prevent repeated DB lookups

}

After a user successfully authenticates, you can create a new session and store it in your database. This session will be looked up on every request, so if you run into performance issues, you should consider storing it in a caching layer. In townsourced, I used memcached, but there are many options available, just as long as the caching layer is available to all of your web servers, otherwise if a user gets load-balanced to a different web server, it’ll look like they’ve been logged out.

package app

...

// SessionNew generates a new session for the passed in user

func SessionNew(user *User, expires time.Time, ipAddress, userAgent string) (*Session, error) {

if expires.IsZero() {

expires = time.Now().AddDate(0, 0, 3) // default expiration

}

s := &Session{

UserKey: user.Username,

SessionID: Random(128),

CSRFToken: Random(256),

Valid: true,

Expires: expires,

When: time.Now(),

IPAddress: ipAddress,

UserAgent: userAgent,

}

s.Key = string(s.UserKey) + "_" + s.SessionID

err := data.SessionInsert(s, s.Key, s.Expires)

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

return s, nil

}

Once your session is created in the back-end, you can store your new session in a cookie in the user’s browser.

package web

...

func setSessionCookie(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request, u *app.User, rememberMe bool) error {

expires := time.Time{}

if rememberMe {

expires = time.Now().AddDate(0, 0, 15)

}

s, err := app.SessionNew(u, expires, ipAddress(r), r.UserAgent())

if err != nil {

return err

}

cookie := &http.Cookie{

Name: cookieName, // const of your app name

Value: s.Key,

HttpOnly: true,

Path: "/",

Secure: isSSL, // global var set if running ssl

Expires: expires,

}

http.SetCookie(w, cookie)

return nil

}

And then on each request, you can check if the session is valid:

package web

...

// get a session from the request

func session(r *http.Request) (*app.Session, error) {

// must iter through all cookies because you can have

// multiple cookies with the same name

// the cookie is valid only if the name matches AND it has a value

cookies := r.Cookies()

cValue := ""

for i := range cookies {

if cookies[i].Name == cookieName {

if cookies[i].Value != "" {

cValue = cookies[i].Value

}

}

}

if cValue == "" {

return nil, nil

}

s, err := app.SessionGet(cValue)

if err == app.ErrSessionInvalid {

return nil, nil

}

return s, err

}

...

package app

...

// SessionGet retrieves a session

func SessionGet(sessionKey string) (*Session, error) {

s := &Session{}

err := data.SessionGet(s, sessionKey)

if err == data.ErrNotFound {

return nil, ErrSessionInvalid

}

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

if !s.Valid || s.Expires.Before(time.Now()) {

return nil, ErrSessionInvalid

}

return s, nil

}

Note how you track expiration on both the client and the server. Never trust anything from the client.

If the client wants to log off, you simply expire the session early (or mark it invalid if you want to preserve the original expiration date).

package web

func logout (w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request, s *app.Session) {

cookie, err := r.Cookie(cookieName)

if err != http.ErrNoCookie {

if cookie.Value == s.Key {

// clear value, and set maxAge: 0

cookie := &http.Cookie{

Name: cookieName,

Value: "",

HttpOnly: true,

Path: "/",

Secure: isSSL,

MaxAge: 0,

}

http.SetCookie(w, cookie)

}

}

if errHandled(c.session.Logout(), w, r, c) {

return

}

}

...

package app

// Logout logs out of a session

func (s *Session) Logout() error {

s.Valid = false

return s.put()

}

That’s it. You should have the basics of managing user authentication in a Go web app. If you skimmed this post, your biggest takeaway should be to not manage passwords, or at the very least, provide your users with the more secure option of using Facebook, Google, or Twitter to authenticate with your app.

The specifics of this post were requested on reddit, so if there are any other topics you’d like covered, or if you found this post helpful, feel free to leave me a comment, or shoot me a message.